A Theory of Agency

Kaushik Basu discusses why human agency is so central to his work and worldview.

Over the course of his career, from Cornell University to the World Bank and the halls of Indian government, Kaushik Basu has found that economic insights often emerge from unlikely sources. In a rural Indian teashop in the 1980s, for instance, he remembers meeting a blind old landowner who practiced share tenancy – a type of land lease contract deemed highly irrational by standard economic theory.

“I explained to the man why share tenancy was irrational, using complicated arguments from economics – but he kept countering,” remembers Basu, the Carl Marks Professor of International Studies and Professor of Economics at Cornell University. “We sat for an hour, sipping tea, and he countered every single one of my arguments, explaining why he wasn’t irrational, despite what the scholars said.”

A few years later, Basu published a paper inspired by the interaction, formalizing the landowner’s arguments. The anecdote reflects Basu’s unique approach to economic research – and why so much of his work has focused, in some form or another, on the concept of human agency.

“Many development economists go to the field, collect massive amounts of data, then analyze it,” he says. “That can be important, but my research is more analytical and my starting point is usually more anthropological. I can learn a lot just from going places and having long conversations with people – in buses, taxis, tea shops, wherever. I try to see things the way ordinary people see them, then take those ideas and give them a formal structure.”

A long path to economics and agency

Born in Kolkata in the early 1950s, Basu wasn’t supposed to become an economist. His father, who had risen from poverty to become a successful lawyer, expected him to eventually take over the family practice. But a brief exposure to economics at the London School of Economics (LSE) transformed his aspirations.

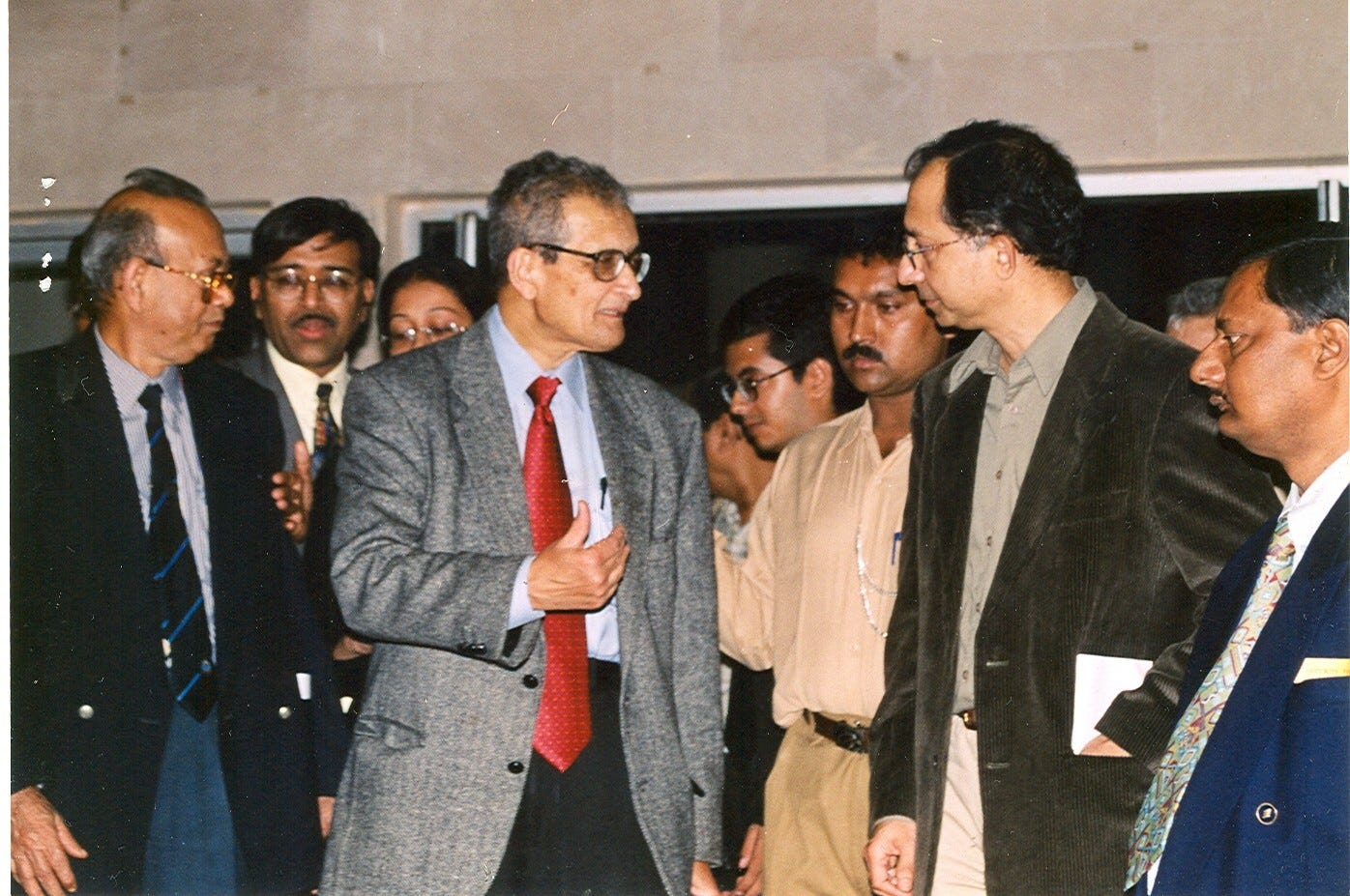

“I felt completely taken in by the discipline,” he says, crediting two professors – future Nobel laureate Amartya Sen and Morris Perlman – with sparking his passion. With his father’s support, Basu pursued an economics PhD under Sen’s supervision. “I really enjoyed the interface of logic and reasoning with philosophy, which was a key interest for Amartya. It got me gripped.”

While teaching at the Delhi School of Economics, Basu’s research agenda blossomed after meeting another legendary economist – Jacques Drèze, who offered him a fellowship in Belgium. There, Basu began combining the strands that would define his career: using economic theory to understand the lives of ordinary people in developing countries.

He recalls two key turning points. In the early 1980s, he read an early English-language draft of Václav Havel’s The Power of the Powerless that had been smuggled out of Czechoslovakia. Basu was struck by Havel’s simple but compelling idea: dictatorships, while appearing large and top-down, are sustained (and dismantled) through ordinary people’s individual beliefs and choices. Basu later formalized Havel’s ideas in a paper on political power, and his 2018 book uses game theory to affirm the moral power of ordinary individuals.

Another turning point was Basu’s 1994 op-ed on child labor in the New York Times, responding to a US bill to ban all imported goods tainted by the practice. While condemning child labor, Basu’s article pushed back on the notion that selfish parents were to blame – noting that few parents would choose to send their children to work, unless they were forced to by poverty and hunger. Later, Basu’s seminal paper with Pham Hoang Van used economic modeling to show why empathetic policy approaches to child labor could be more effective.

An up-close look at economic policymaking

From 2009 to 2012, Basu left academia to serve as Chief Economic Adviser to the Indian government. It was a stark contrast from academia, but Basu navigated the experience in much the same way as his approach to economic research.

“I treated myself like an anthropologist in Delhi’s bureaucracy, observing the policymakers and politicians,” he says. “As a scholar, you can criticize a particular policy. But once you go in and really listen, you realize that policymakers are just human beings like the rest of us, grappling with similar problems – but the collective nature of their situation has them trapped.”

The experience had a strong influence on Basu’s future work. He was a co-author, for instance, of the Stockholm Statement, which advocated for taking context – including people’s behavioral and psychological contexts – into account when designing policies. Later, he co-founded the Cornell Research Academy of Development, Law, and Economics (CRADLE), which seeks to help bridge the gap between academic economists and developing-country policymakers.

Bringing behavioral economics to the World Bank

After his government work, Basu served as Chief Economist of the World Bank from 2012 to 2016 – a role with significant influence on global debates about economic development. During his tenure, Basu advocated for a human-centered approach to economic analysis and policymaking, arguing that economists should take socio-cultural complexity and human behavior more seriously.

In particular, he was instrumental in the World Bank’s 2015 World Development Report on “Mind, Society, and Behavior.” The report was one of the World Bank’s first major publications to incorporate insights from psychology, sociology, and behavioral economics – but it almost didn’t happen.

“It was quite a battle at first,” he remembers. “A lot of people said, ‘This isn’t economics! What can economists say about all this?’ But I argued that economics was embedded throughout these issues – and unless you understand the embeddedness of economics, you’ll make the wrong economic policies.”

The report brought behavioral economics into mainstream development thinking, at the World Bank and beyond. Co-directed by Karla Hoff and Varun Gauri, it gathered cutting-edge research from a wide range of disciplines, showing how people’s decisions and behaviors – and their personal agency – are strongly influenced by social norms, mental models, and cognitive biases. Even small changes to a given context or situation can have large impacts by influencing how people perceive their choices and respond to incentives.

“Economic behavior is triggered by many different wirings in our brains,” says Basu. “Simply put, things matter that you might not think would matter.”

The report argued that recognizing these insights is critical for designing more effective development strategies – highlighting numerous examples of how insights from behavioral science have improved outcomes across health, finance, education, energy consumption, gender empowerment, and a range of other areas. This evidence suggests that programs, policies, and institutions can all be designed to nurture individual agency, rather than constrain it, often through small and relatively costless tweaks.

One of Basu’s favorite examples is a study showing that making Indian students disclose their caste can significantly decrease academic performance. By recognizing such “stereotype threats,” schools – and other public sector institutions, from hiring units to health clinics – can take small steps to alleviate them. Likewise, during the heights of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large share of low-income families in the US did not apply for emergency support programs because they saw themselves as self-sufficient workers. Would take-up have been higher if the programs and their messaging had been designed to support recipients’ sense of agency?

Another highlight of Basu’s time at the World Bank was the 2017 World Development Report on “Governance and the Law,” which is similarly credited as a breakthrough study on governance. That report also had personal resonance for Basu, given his experiences studying law and working with India’s government.

The moral dimensions of agency

After decades of studying how individual agency, choice, and behavior interacts with economics and development, Basu recently turned to a broader concept: group agency. Combining economic theory with insights from philosophy, this line of research seeks to analyze the moral dimensions of group behavior.

“An individual’s ability to act is often very different from what the collective can do,” he says. “Game theory gives us the prisoner’s dilemma, where selfish individuals have incentives to make decisions that are bad for the group. But how can morally conscious individuals improve outcomes for the entire group – and for future generations?”

Largely inspired by the global climate activism movement, this work reflects the converse of Basu’s interest in Havel: even when large groups of individuals share similar moral beliefs, why does that so often fail to dismantle harmful systems? It also links his initial economic research, inspired by Amartya Sen’s capability approach, to broader moral frameworks, from Aristotle to John Rawls and contemporary philosophers.

“Ultimately, group agency requires individuals with moral intention but also intelligent design,” he says. One set of examples supported by evidence is political reservation policies to ensure adequate representation for historically marginalized groups. While a number of countries have implemented such policies, India’s 1993 constitutional amendment to reserve a share of locally-elected leadership positions (pradhans) for women is perhaps the most prominent. The change has been found to be associated with a range of positive effects in terms of gender empowerment and equality, including improvements in Indian women’s self-perceptions, aspirations, and behaviors (e.g., running for and winning public office).

“Morally conscious people need to also think about the agreements and constitutions that form the architecture of society,” Basu says. “We live in a globalized world, so we have to think collectively about global rules, and they must be designed intelligently – to help society give expression to the agency of goodness that you want to bring about.”

Written by Greg Larson.

This blog is part of a series on Leveraging Personal Agency for International Development, a convening co-organized by The Agency Fund and the SEE Change Initiative at Johns Hopkins University, where Basu delivered a keynote address.