Over the past two decades, the field of international development has made great strides in determining which aid programs and social policies are effective at improving standards of living in the Global South – including notable efforts in the psychological and behavioral sciences. Yet this literature is also replete with examples of carefully organized, well-funded, and empirically backed development programs that falter or fail to capitalize on their promise.

Examples abound. For instance:

In Malawi – despite evidence that unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) offer wide-reaching benefits for people experiencing poverty – villagers refused UCTs because some members of the community were excluded.

In Sudan, food aid given to people at high risk of starvation was rerouted to their chief to communally allocate, resulting in whole communities’ slow starvation.

In India and China, an approach for motivating students by visualizing personal aspirations and making concrete goals – robustly shown to enhance academic engagement in the United States – failed.

What might explain so many failures alongside development’s many successes? Some answers might be found by taking a cultural lens. The examples above suggest possible cultural mismatches between the design of programs and the sociocultural features of the populations they seek to reach. International development is ripe for such mismatches, given that people from very different cultural backgrounds influence program design and that most evidence from the social sciences to date (including ninety percent of psychological research) comes from high-income, Western contexts.

This blog explores these fundamental tensions, highlighting recent evidence and offering guidelines for how to practice “culturally attuned” development.

Why culture matters in development

Recent years have seen an explosion in the “science of international development,” marked by the increased use of experimental evaluation techniques – including a growing share of studies focused on the psychological and behavioral dimensions of development. Such efforts have generated a wealth of evidence regarding which development programs and social policies are effective at improving standards of living in different contexts across the Global South.

But many of these efforts originate from cultural contexts that researchers collectively refer to as Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD). These high-income and largely individualist contexts typically rely on independent models of selfhood and agency, centering on personal goals and values, self-advancement and self-expression, and individual autonomy and choice.

Yet at the global level, WEIRD cultural contexts are highly atypical. In the low-income contexts where most development programs are implemented, an interdependent model of agency is far more predominant. People experiencing poverty often rely on tight-knit social networks to cope with resource scarcity – with ways of being centered on relational goals and values, social coordination, and responsiveness to social norms, roles, and obligations.

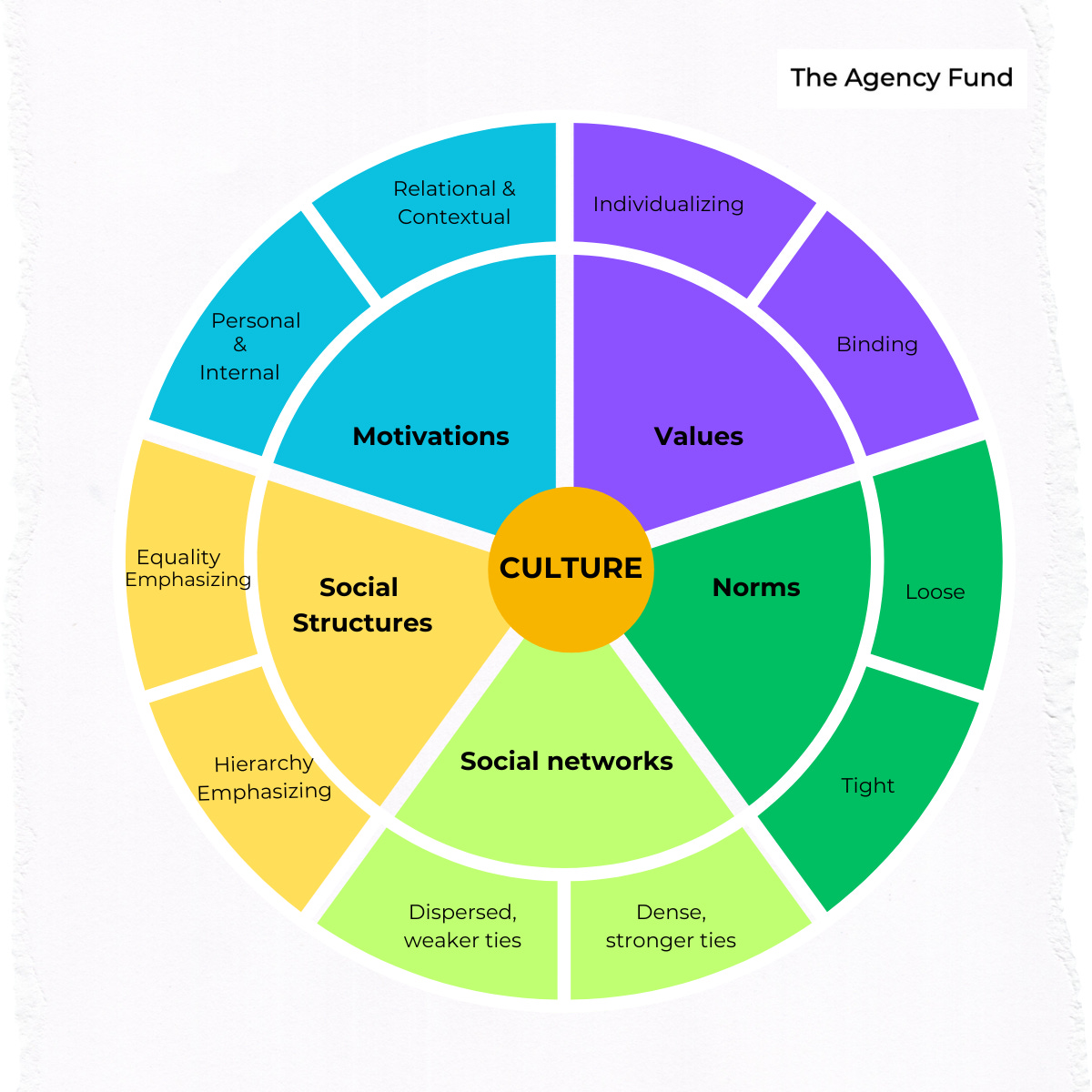

In a recent paper with Hazel Markus, we identify some of culture’s key dimensions and how they manifest differently across contexts with independent or interdependent models of agency. Here, I highlight five:

How cultural mismatch weakens effectiveness

The above figure’s outer ring underscores development’s key cultural tension. Given the WEIRD skew of social sciences, there is often an underlying assumption in the design of many development programs that human agency and behavior is more independent. This perspective views people as independent actors driven by personal and internal motivations, equality-emphasizing social structures, individualizing values, loose norms, and dispersed social networks – yet such programs are typically implemented in communities with highly relational and contextual motivations, hierarchy-emphasizing social structures, binding values, tight norms, and dense social networks.

Too often, such cultural disconnects reduce development’s potential. Programs based solely on independent models of agency can limit their scope and effectiveness – and in the most adverse cases, they can be met with resistance, backlash, or even violence.

These concerns are relevant for any development effort, but they are particularly important for programs that seek to enhance human agency. Initiatives to boost motivation, self-confidence, self-efficacy, and agency’s other facets have been shown to have positive effects on a broad range of development outcomes, from educational attainment to health-seeking behaviors. But agency takes a vast array of forms – as variable as the contexts that give rise to it – and different forms and combinations are productive for different contexts and goals.

A growing body of literature supports the critical role of cultural differences in development. In rural Niger, for instance, my collaborators and I find that low-income Muslim women see women’s economic success as fostered primarily by respect for others and peacefulness, both with others and within the self – rather than individual goal-planning, persistence, or hard work. When these women were randomly assigned to a brief social psychological intervention that framed women’s economic activities as either (i) a process of personal initiative, goal pursuit, and self-advancement or (ii) a process of social solidarity, respectfulness, and collective advancement, only the latter led to improvements in economic outcomes after a year.

Likewise, when comparing East Asian and South Asian contexts to the United States, recent research finds that fulfilling social obligations is relatively more motivating than achieving personal autonomy.

All this points to the need for more culturally responsive and informed approaches to development. But how?

Practicing culturally attuned development

The first step is to take cultural context seriously, especially with respect to psychosocial tendencies, practices, and values. Only by expanding our models of human agency and behavior can we design development programs for interdependent orientations.

As a start, the following five questions can help identify common sources of cultural mismatch:

Motivations and Values:

Relational goals and binding values: Is the program responsive to the community’s prevailing goals and preferences or does it ask participants to prioritize their personal interests, rights, and goals?

Fulfilling relational obligations: Will program participants be able to fulfill important social roles, duties, responsibilities, and obligations or will they be asked to neglect or violate them in favor of personal interests and goals?

Social Norms and Networks:

Tight norms: Will program participants fit in with (or stand out from) their peers?

Embedded networks: Relatedly, will the program strengthen (or strain) participants’ close relationships with other family and community members? Will the program maintain cohesion or cause conflict, jealousy, or envy?

Social Structures:

Honor, respect, and tradition: Do community members with authority approve (or disapprove) of the program? Will program participants be seen as honoring and respecting (or dishonoring and disrespecting) their family and/or social unit? Will participation entail respecting and preserving (or disrupting and disrespecting) their lineage, history, and time-honored traditions?

To generate answers to these questions, program designers can collaborate with the program’s intended participants and local experts through qualitative (e.g., interviews, focus groups, sorting exercises) and quantitative (e.g., surveys, experiments) methods. The questions can also be used to construct context-specific metrics for assessing whether programs are culturally responsive and identifying ways to make them more so.

How to work with interdependent mindsets

Often, designing programs that respect, respond to, and work with (rather than directly confront) interdependent mindsets is just a matter of reframing goals or shifting focus. This is even true for programs that seek to shift certain aspects of culture, such as the gender hierarchy. Consider these four examples, drawn from my work with Stanford’s “Social Psychological Answers to Real-World Questions” (SPARQ) team:

“Saving money is selfish”: People with interdependent mindsets often believe that accumulating personal wealth betrays their family and/or community – in such contexts, culturally attuned programs can reframe savings as “helping children and elders thrive in the future.”

“Women entrepreneurs are out of line”: In contexts where women have clearly defined roles that are practical and moral, programs can reframe efforts to improve home finances as aligning with local values, such as care for children and leaving a legacy.

“Trust wisdom, doubt innovation”: In contexts where rejecting traditional wisdom is seen as foolish and arrogant and strangers are distrusted, programs can enroll elders or role models to approve of or participate in new practices and technologies.

“Planning is blasphemous”: In contexts where trying to control the future is seen as irreverent and hubristic, programs can present planning as “preparation for shocks that could threaten the family or community’s security and wellbeing.”

While such simple tweaks might seem minor, the emerging evidence suggests that culturally attuned development can have profound and powerful effects. In addition to advancing program effectiveness, such approaches can advance the goals of equity, inclusion, and decolonization more broadly. Beyond expanding access to health, wellbeing, and prosperity, culturally attuned development offers the promise of a more comprehensive account of human behavior – through practices that embrace, rather than ignore, the world’s rich cultural diversity.

This blog is part of a series on Leveraging Personal Agency for International Development, a convening co-organized by The Agency Fund and the SEE Change Initiative at Johns Hopkins University.